Spy Balloons! And Space!

Using film from U.S. spy balloons to take pictures of the Moon

While America is going crazy over a Chinese spy balloon, I’m featuring a relevant and a way more fascinating story from an old school internet site.

Without going deep into the Luna 3 mission (the linked site provides plenty of depth), the primary problem the Soviets were facing was time: get it done as soon as possible.

By the autumn of 1959, orbital space flight was turning 2 years old. To be the first to image the far side (and thus name craters n’ shiet) the milestone to pass was an extra, well-executed trans-lunar boost from low Earth orbit to make a probe fly past the Moon at the right time (when the far side is sunlit), with the right orientation (pointing the cameras at the Moon).

The Americans were behind, but catching up fast, and this extra, trans-lunar step wasn’t too difficult to make for a competitor who had already achieved LEO by early 1958.

The next problem was image capture and transmission back to Earth: the Soviets decided to use a film camera, develop the film inside the probe, then transmit the pictures back with a TV camera.

Of this complicated setup, every part could be made to work in deep space: pressure and temperature could be maintained for the duration of the mission inside the probe. You can spin it up if you need liquids to behave. Everything could be made to work, except one part: the film.

I figured ... We will not get any picture. To protect the film from cosmic radiation requires a half-meter layer of lead. How many do you have? 5 millimeters.

There’s no way to shield photographic film properly for the duration of a trans-lunar flight (2+ days). Film fogs up in a radiation environment, somewhat by design; film is used in the simplest of personal dosimeters, sealed badges, where it is protected from visible light, so any exposure it receives while worn can only be from penetrating radiation.

I had big doubts about the photographic film that we used - "Type 17" (manufactured by Shostka). For aerial photography it was quite suitable, but for the cosmos a much greater sensitivity was required. I was also afraid that the film would be strongly veiled due to cosmic radiation. What to do? Again bow to NIKFI [Cinema and Photo Research Institute, Moscow], with which we were so much in disagreement? Impossible. And time was running out. And then a completely crazy thought occurred to me ...

Up until 1959, when imaging the lunar far side became their target, the Soviets had no need to develop a photographic medium that can sustain an extended period in a radiation environment without fogging up, while also remaining sensitive enough for short exposures of visible light.

The Americans on the other hand had this need, for use in their high altitude spy balloons. Starting from 1955, they would send these over Asia, hoping that they will cross over important sites, flying at an altitude of 15-30 kilometers.

Our anti-aircraft gunners shot down these reconnaissance balloons in batches. Samples were transferred to Mozhayka, with whom I maintained close business relations. The photographic equipment used for the balloons was of no interest, but the film, created for shooting from high altitudes, was good.

Spending days at an altitude of 15 to 30 kilometers is quite the radiation exposure (and those films also had to make it back before development, suffering additional dosage).

There’s of course all sorts of radiation, in high altitude, in space, within the Earth’s magnetosphere and outside of it (we can assume Luna 3 went outside Earth’s magnetosphere, as the Moon was between the Earth and the Sun), and not all should affect film the same way, nor should all kinds of film be affected the same for a given type of radiation, but for the sake of simplicity, just accept that the higher you go, the more radiation you receive, and the highest you can go is space. Yes, there are radiation belts but just keep it simple, like the Soviets do when they want to get things done, and in 1959, the scientist working on Luna 3 wanted a very specific mission to be successful: imaging the lunar far side.

Being at the dawn of the space age, these scientists themselves weren’t sure about the radiation environment, or its effect on any specific type of film. The American spy balloon stuff had the best chance to succeed, and time was short:

If I had only hinted to someone about the possibility of using an American film, I would be mistaken for a foolish joker or even for a person who was not completely normal. Only two people knew about this venture - me and Volodya Kondratyev, who was engaged in the chemical processes of the Yenisei. We cut an American 180-millimeter film to 35 millimeters, then punched it. We wrote "technical conditions of the film type AB-1", which after having been shown to the military representatives was filed in the appropriate folder with the stamp "top secret". Of course, we both stayed silent.

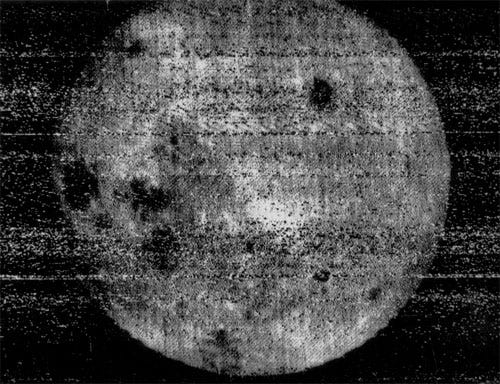

Finally, there were shouts: "There it is"! The first lines were dark, but then the invisible side of the moon with its craters and seas began to open more and more. Embrace and kisses began, and the entire "picture" slowly emerged.

And the fact that we "photographed" the opposite side of the Moon with an American film that was sent to our country with purely spying goals, I told my closest associates only many years later, long after the untimely death of Sergei Pavlovich Korolev. In fifteen years. The abbreviation AB, I think, is not necessary to decipher. Of course, it is "American Balloons".

Science!